⬅️ Books

Written by Min Jin Lee Read in July 2022

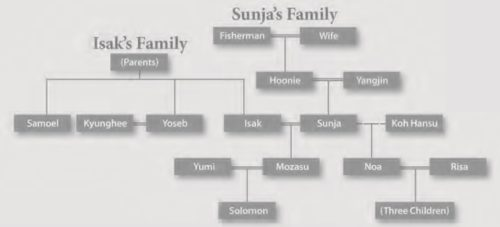

A story of a Korean family through four generations (1910 - 1989). Their struggle - WWII, divided Korea - and their experience of living in Japan as second-class citizens.

It’s about family, loyalty, values, principles, hard work and hope. And sadness and pride, and shame. And dreams.

Koreans in Japan had it rough, always looked down on as lazy, stupid, smelly (the kimchi and just generally more garlic) and gangsters. That’s why one of the only good jobs they could get was to work in a Pachinko parlour (arcade & gambling parlour mix).

Beautifully written. Simple yet profound. Leaves you with a lingering feeling of loss.

Also an Apple TV series

- a sweeping historical saga of one family’s experience living as “forever foreigners” in twentieth-century Japan

- set in a particularly rich era of modern East Asian history, encompassing colonial Korea, World War II, the Allied Occupation of Japan, the Korean War, and Japan’s high-growth and “bubble economy” periods

- we view events exclusively from the perspective of the main characters, ordinary people with a very limited understanding of the world beyond their immediate experience

- Japanese-born Koreans were left essentially stateless following the resumption of Japanese sovereignty in 1952—even if they had never been to their “home” country and spoke no Korean

- Despite the family’s financial prosperity, their future remains capricious—much like a game of pachinko, in which small metallic balls fall randomly down a maze of pegs, sometimes landing in a winning hole but more likely falling down to the bottom.

In the opening lines of the novel, Lee notes that “history has failed us, but no matter” (5). I believe here the author refers to what we might think of as “history with a capital H”: that is, the study and teaching of the subject, rather than the ceaseless unfolding of events over time. In that sense, she is correct—too often have we relied upon the standard narrative of the period (World War II, the Korean War, Japan’s “economic miracle,” and so on) and neglected those ordinary yet extraordinary people who lived in the interstices of empire, at the margins of their own societies, and as men and women without a country. For the history teacher—for any teacher—Lee’s work thus represents both a challenge and an opportunity.

Spanning nearly 100 years and moving from Korea at the start of the 20th century to pre- and postwar Osaka and, finally, Tokyo and Yokohama, the novel reads like a long, intimate hymn to the struggles of people in a foreign land.

Shame and guilt underpin many of the finest scenes in the novel, with every character continually forced by their position as second-class citizens to make painful sacrifices, and, consequently, to consider the nature of those sacrifices.

Resources

- https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/contextualizing-min-jin-lees-pachinko/

- https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/15/pachinko-min-jin-lee-review